Cultural legacies, with their inevitable potential for controversies compounded by competing claims between contending nations, can be fraught affairs. Disputes over art works and artefacts of one country being found in another are legion. The UNESCO convention, which mandates return of illegally acquired objects to country of origin when provenance is established beyond doubt, is actually an acknowledgement that disputes are bound to persist and, therefore, require a basis to be addressed.

Although there are numerous instances where countries have resolved disputes over cultural objects in an amicable manner, many a long-running controversial case remains unresolved. One of the best-known cases is that of India’s fabled Kohinoor diamond.

Taken away by Persia’s Nadir Shah and brought back by the Sikh ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh, under British duress, his son Duleep Singh “presented” it to Queen Victoria in the 19th century. Britain claims ownership saying it was a gift. This is disputed by four other claimants, namely, India, Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan.

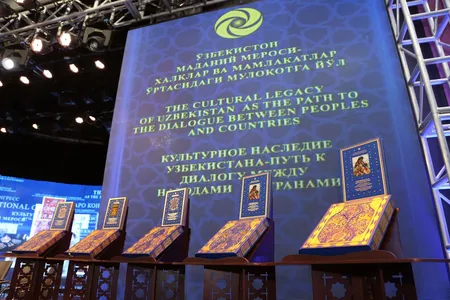

In sharp contrast to such running feuds, which periodically make headlines with a new twist or turn, Uzbekistan’s initiative to use cultural legacy as the path to dialogue between peoples and countries is truly ground-breaking. Nearly 220 international scientists, scholars, experts and museum heads – including 120 from at least 15 countries -- gathered for an International Scientific Congress on Cultural Legacy held over two days in the Uzbek capital of Tashkent and its ancient city Samarkand.

Supported by the UNESCO, ICOMOS (International Council for the Preservation of Monuments and Sites) and Germany’s Konrad Adenaur Foundation, the Congress’ agenda was to discuss ways and means of reinforcing cultural legacy as the basis for dialogues between nations.

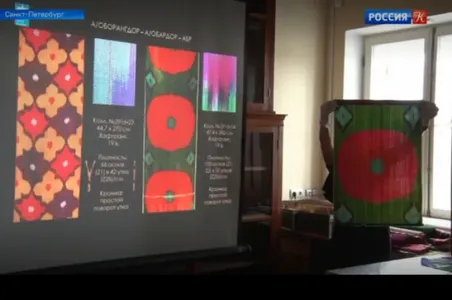

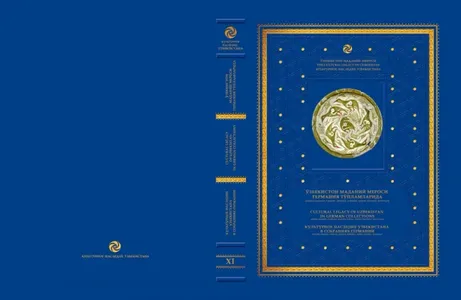

Such conversations would require in-depth study, research and documentation of any one country’s legacy in other countries; and, the process itself would mean dialogue, cooperation and wider popularisation of the material and artistic culture of the countries involved. It was resolved to make the Congress an annual event, and a permanent Scientific Committee has been set up for this purpose. A number of reports and papers – on various studies of Uzbek material and artistic objects, traditions and practices in various countries – presented at the Congress are to be published.

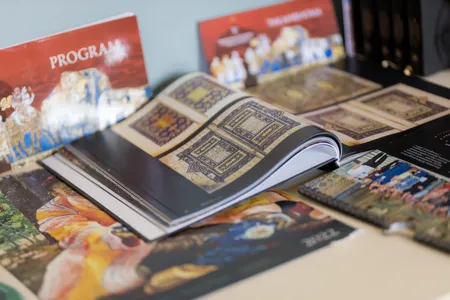

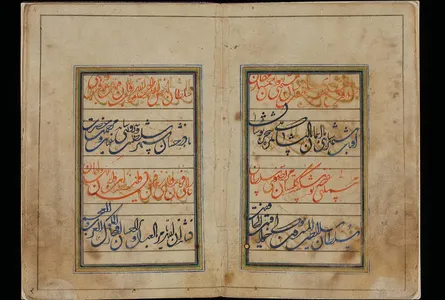

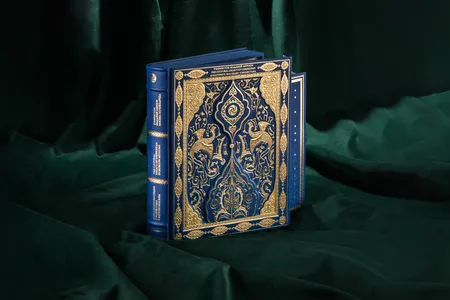

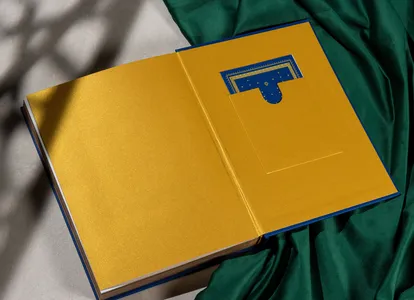

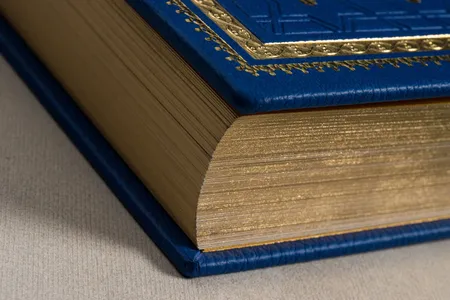

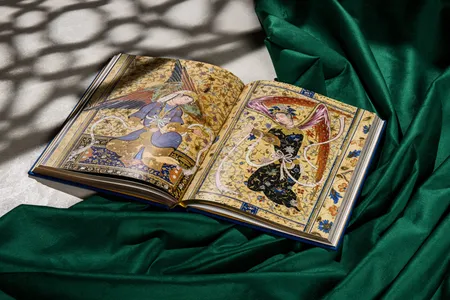

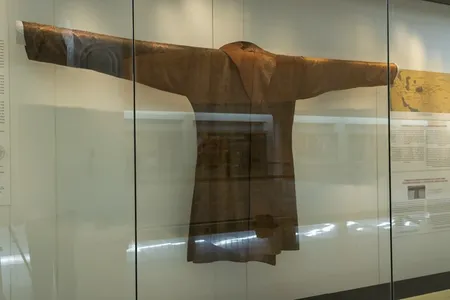

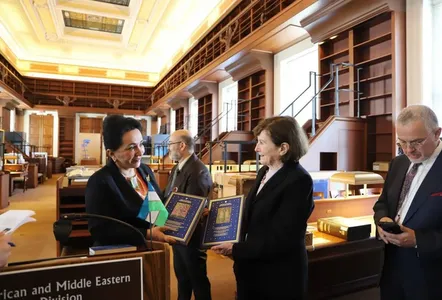

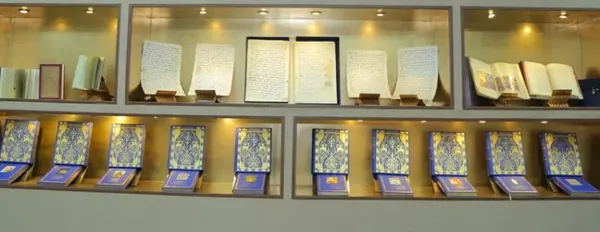

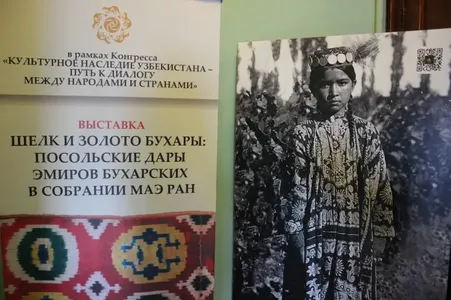

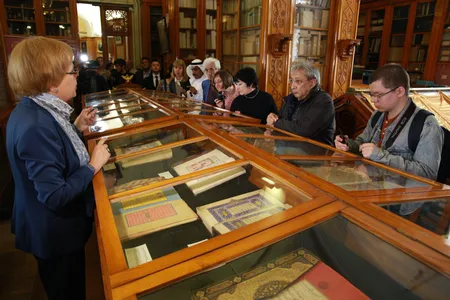

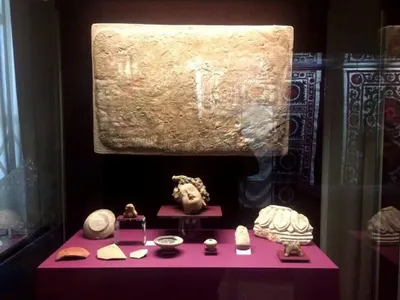

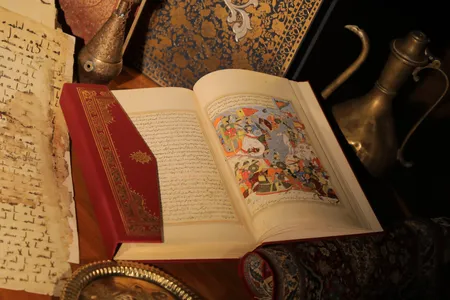

In pursuance of the objective of cross-cultural dialogues, Uzbekistan has brought out 10 volumes, and several short films, on the Cultural Legacy of Uzbekistan in the Collections of the World. These excellent volumes in Uzbek, Russian and English on Uzbek collections, including in leading museums, in Russia, North America and Australia have been authored by well-known art historians, Orientalists, musicologists, archaeologists, curators and scientists. They are packed with visuals and comprise rich material hitherto not published in one place, said a delegate to the Congress. Almost all the delegates this writer spoke to were fulsome in their praise of the publications and their usefulness; which would, doubtless, encourage the continuation of the projects to bring out more book albums and films.

“I am impressed by the quality of their publications on heritage. As it is impossible to return objects from museums and collections in the world to the country of origin for a variety of reasons, the book project gave Uzbekistan an active role to engage with their heritage,” Dr Christoph Rauch, Director of the Oriental Department at Germany’s Prussian State Library in Berlin, told this author. In fact, many delegates said that it was a good idea which other countries could emulate.

Alexander Wilhelm, university lecturer and publisher working out of Spain and Germany welcomes the fact that the project of publishing albums would be continued. “I am a publishing man. So, in my opinion, publishing is fundamentally a good thing. To present information about peoples, their way of life and legacy, and cultural achievements is a necessary step to initiate and enlarge mutual understanding. And, it can help to prevent conflicts.”

Dr B R Mani, Director-General of India’s National Museum in New Delhi, told IDN that the Congress was a focused and purposeful exercise. Perhaps, no other country has done a worldwide survey of objects from their culture as Uzbekistan has done in a short period preceding the Congress. “What Uzbekistan has done is a good idea. It should be done by other countries also. I wish India, too, would do something on these lines. After all, there are tens of thousands of material and artistic objects from India in other countries,” Dr Mani said.

He felt a survey followed by reports and publications of objects and their locations are more important than the question of to which country these belong and the attempts to retrieve them. “This Congress and the thinking it has set in trend are not about securing the return of heritage objects, although there are people and countries that want it back,” Dr Mani said.

An expert from Central Europe said once the tendency to accept cultural legacies as common heritage of humanity, regardless of borders, gains ground, more countries would be open to sharing what is in their possession. “The secrecy surrounding some of the prized objects and their origin will also go.”

A delegate from the UK, who did not wish to be identified, said that the desire for wanting objects back, at least in some cases, belongs to a mindset of “outdated nationalism”. He felt that in a globalised world, it would be more appropriate to treat cultural legacy as “common heritage of humanity” and commit to allowing universal access. This led to an animated discussion, off the record, among a select group of experts on the merits of letting the objects remain where they are vis-à-vis the urge to ensure that it goes back to its native cultural habitat.

Dr Rauch observed that nations are a relatively young idea, which is already challenged in many parts of the world. “I don’t think heritage belongs to certain nations, as cultural borders are not identical with borders of modern states.”

Publisher Wilhelm, who made a presentation at the Congress, is optimistic about the avenues opened up by the event and exchanges. He is convinced that ‘Cultural Legacy’ is a very good platform for dialogue. “Getting to know each other is the best path to mutual understanding. Presenting one’s own past and achievements – with flaws and all -- helps to better understand different cultures. The unknown is always suspicious, if not ‘dangerous’. If I get to know my neighbours, both near and distant ones, fear disappears and understanding grows.”

He said that the Congress enabled participants to know Uzbekistan better. This understanding has created channels for even more communication of the Uzbek legacy to the world. The Congress, he said, has speeded up existing – and, even started new -- scientific projects, which is good: more knowledge is always an advantage and reduces the danger of misunderstanding.

The effort is also expected to boost tourism, especially heritage and cultural tourism. Dr Rauch said that one of the main aims of the Congress is surely to promote Uzbekistan as a world tourism destination. “Uzbekistan is a young state and they need such big congresses also for strengthening their identity,” Dr Rauch pointed out.

Another historian, who wants to remain anonymous, endorsed this viewpoint, adding that after the break-up of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan and Russia seem to enjoy a “comfortable relationship” and a “healthy equilibrium” which has not made cultural legacy a contentious issue with potential for conflict – as, added another participant, has been the case between many independent developing countries and their former colonial rulers.

Wilhem says there are risks though, because cultural legacy is also a fraught issue. The same legacy claimed by different cultures is potentially dangerous. “Some historical events are seen differently by different people. That´s why, I think, it is a good idea to stick to the ‘cultural side’ and exclude potentially dangerous political-historical events,” he added.

As K Rahman, Assistant Curator of Arabic Manuscript in India’s National Museum, observed in his feedback to the Congress: This seminar was a platform for scholars and experts from all over the world to share their knowledge and expertise with respect to the Uzbek legacy, highlighting its oral, visual and literary culture. The experience and exchanges are bound to trigger new paths of collaboration that may not be limited to Uzbekistan’s cultural legacy but extends to encompassing other peoples and cultures.

*Shastri Ramachandaran is a senior editor of IDN-INPS and independent commentator on regional and global affairs based in New Delhi. He travelled to Tashkent and Samarkand for the International Congress on the Cultural Legacy of Uzbekistan at the invitation of The National Association of Electronic Mass Media of Uzbekistan. [IDN-InDepthNews – 23 May 2017]