They excel in their high weaving density, perfectly sheared pile, deep and balanced palette, and elegant ornamental compositions. The earliest of the preserved Uzbek sheared carpets were woven on a narrow-bean machine just like julkhirs, and consisted of finished panels that were then sewn together. For Uzbek tribal groups, it is likely that solid-woven, sheared carpet was a later phenomenon.

The most famous areas of this carpet’s production were the Samarkand and Jizak regions, Nurata Intermontane region, Kashkadarya and Surkhandarya, and the Fergana Valley. Samarkand carpets make up a group of items that vividly reflect the authentic style of Uzbek weaving. They preserve the ancient astral and totem symbols that are equally valued in the art of all ex-nomadic peoples. The most popular medallion in Samarkand carpets with different variations is an equal-sided cross with a rhombus in the middle and horn curls on the ends, which was likewise widely used in flat-woven weaving (kaikalak or kuchkorak). Another classical motif is the stepped rhombus with an octactinal bud or horn-shaped motif, surrounded by 12 horn curls – this motif can be found on covering carpets, including julkhirs, as well as other carpet cloths.

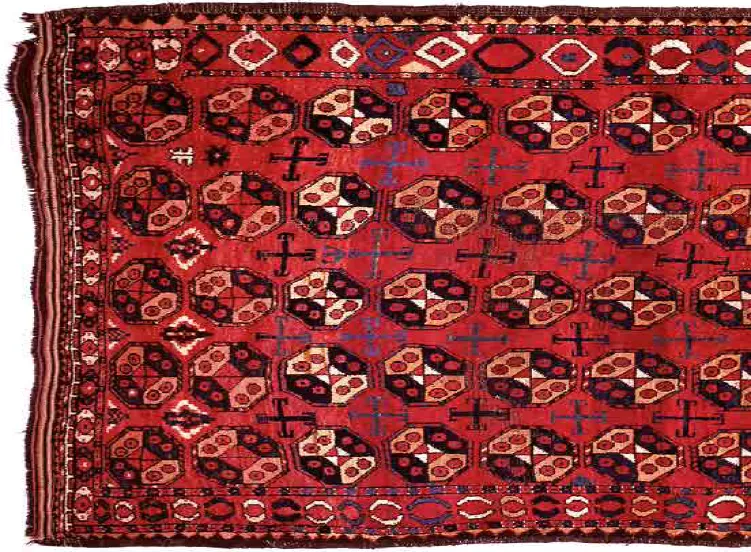

The kholi carpets of the Uzbek-Turkoman from the Nurata Intermontane region are immediately recognizable thanks to their large medallions, known as kalkan-nuska. These medallions were arranged in two to three rows in the central field. The medallion’s base is octagonal (a square with chamfered corners) divided crosswise into four equal sectors. Each sector has a kalkan – or a semi-abstract image of a four-legged animal with a head and split tail resembling two little horns. This image can be associated with either a bird or a hoofed animal.

According to V. G. Moshkova, it was once called at, meaning horse. “On the cross lines sectioning off the medallion, there are two bird-like images. One of them has a bird-like head on a long neck with very round shoulders, while the other has the same head on a shorter and thicker neck. The lower part resembles either widely-spaced legs or a wide base or body. This element was sometimes replaced with a pair of horns. ...These elements are called kush (bird) or kuchkorak (horns). Some weavers reinterpreted these motifs and called them chomych (dipper with a long handle) and samovar, on account of their formal resemblance”.

Another popular medallion in Nurata carpets was muiyz-nuska (horn motif), based on the traditional steppe art element of an equal-sided cross with kaikalak (kuchkorak) horn curls, which underwent a certain transformation. In their depictions of crosses with horn curls inscribed in a square or rectangle, weavers used color to draw attention to the background between the cross ends, thus adding a completely new perceptive angle to the design: the background becomes a pattern, while the pattern becomes a background. Sheared carpets were likewise produced by the Kungrat. By the mid-20th century this tradition was on the decline, and current museum collections can boast of only rare examples of Kungrat pile carpets. With all the variety of compositions and ornamental motifs in Uzbek pile carpets, a certain similarity of style can also be noted, including the geometrical pattern, contrast of ornaments and background, active usage of contouring line that accentuates the image’s expressiveness, and red and brown palette in combination with indigo. The pattern features ornaments typical for flat-woven items and for steppe culture in general, such as cosmogonic symbols, totemic signs and tribal tamgas.

You can learn more about the topic in the book-album "Carpet making of Uzbekistan: A tradition preserved through centuries" (Volume XIV) in the series "Cultural Legacy of Uzbekistan in the World Collections".

The main sponsor of the project is the oilfield services company Eriell-Group.